The fishing community in Poole has watched its fleet undergo several transformations. Fish stocks once seemed endless, and so did the number of vessels. But recent decades have seen a steady decline. In the early 1990s, thanks to government policy on fishing quotas—the share of the catch limit allowed to any given vessel—a number of fishers were shut out of the system. Many of them left the industry altogether.

With Brexit, another transformation is on the cards, and once again ports like Poole stand to lose out. For this fishing community, Brexit may well not turn out to be what was advertised on the tin.

During the referendum campaign last year, “Leavers” made a lot of noise about Britain’s fishing industry and how it stood to gain from EU exit. The most headline-grabbing example was when Nigel Farage led a flotilla of fishing trawlers up the Thames in a protest designed to coincide with Prime Minister’s Questions. And in the end, many fishers did opt for Brexit, enthusiastic about an end to EU regulations and quotas which, in their view, meant foreign trawlers were netting all their fish.

But here’s the thing: the risks and opportunities presented by Brexit depend largely on which part of the fishing community you consider. For there is not just one “fishing industry.” And the potential benefits presented by Brexit are highly concentrated in a few hands.

Fishers in Poole are reliant on exports. Most of the £2m worth of fish landed there each year is shellfish for export. This includes whelks and oysters for the Asian market and clams, mussels, crabs and finfish for the EU market. In fact, Poole serves as point of export for fish from several nearby ports en route to fish markets and restaurants in France and Spain. Fishers here are keen to sell to the British market, but British tastes are infamously stubborn. Poole is therefore put significantly at risk by any Brexit which creates barriers between the British and European markets.

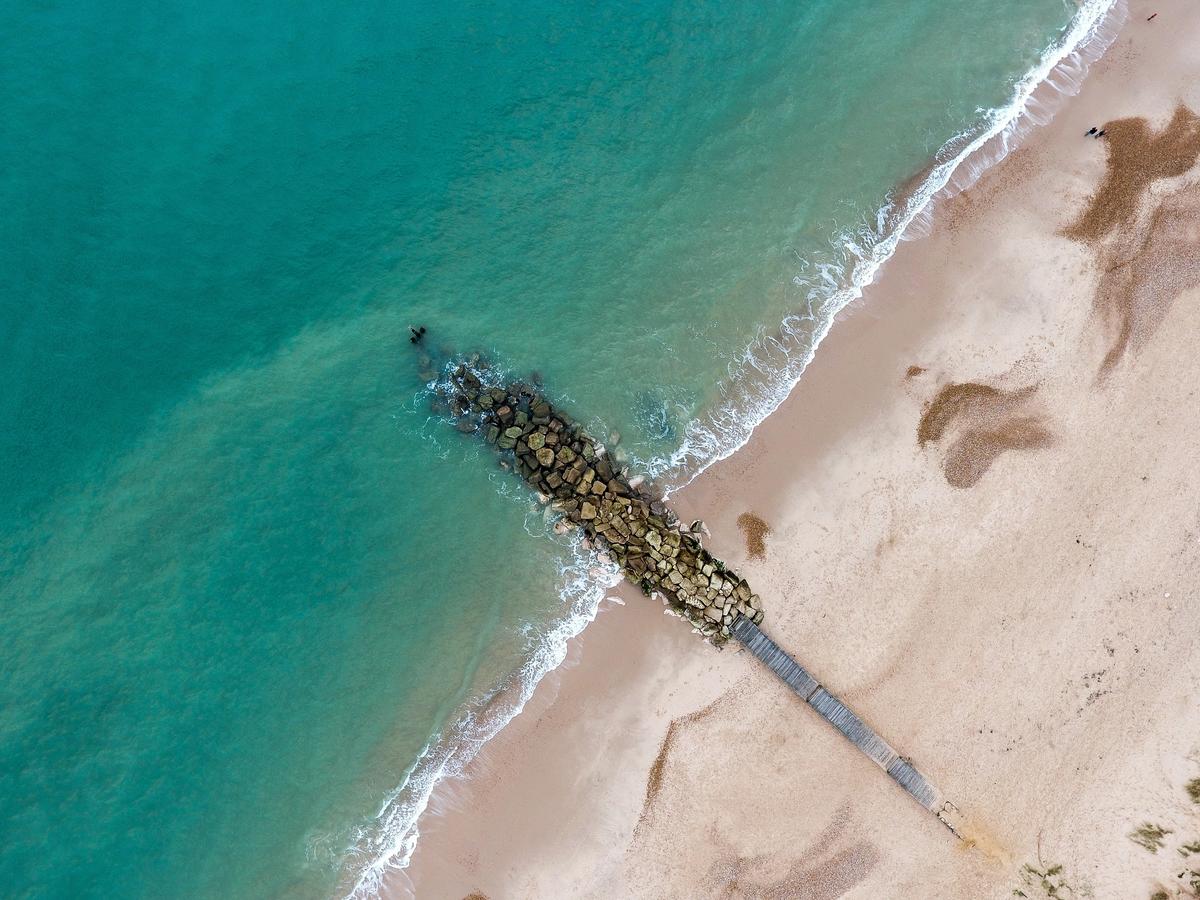

It is particularly exposed because its fleet is small-scale, with all 79 vessels under 12 metres in length. Some British vessels stand to benefit if post-Brexit fishing quotas are increased, as they hold the quota shares. But the ships in Poole, largely shut out of the quota system, would not. This supposed advantage of leaving the EU is not much help for them at all. Nor are these small-scale vessels going to be fishing out to the limits of the UK’s territorial waters anytime soon.

Of course, the community in Poole is just one example. My recent impact assessment of Brexit on the UK catching sector for the New Economics Foundation revealed that around half the UK fishing fleet consists of small-scale vessels that catch shellfish, without quota, for the EU market—and so would not benefit from “opportunities” presented by Brexit.”

It’s not just fishers themselves who could lose out here. The final deal Britain strikes with the EU will be crucial to those working elsewhere in the industry. But with the Article 50 countdown underway, the government is yet to agree on what “end state” it wants. Alarm bells are beginning to ring.

The fish processing and wholesale industry—closer to the point of export than fishers themselves—has been the first to sound off. Grimsby, one of the largest fish processing centres in Europe, hit the headlines recently with its request for a “Brexit exemption,” seeking “Free Port” status to allow it to continue to sell large quantities of processed fish to the European Union on zero tariff terms. Similar campaigns in Hull and Port Talbot are in the works.

Grimsby’s request was dismissed, even ridiculed, in much of the media coverage, but there’s a very serious point here. These are real people and real jobs, and the consequences of Brexit are not to be scoffed at. Young’s Seafoods, the largest employer in Grimsby, announced earlier this week that it is up for sale. Change is afoot, and many parts of the fishing industry, and the communities that are employed in them, are at risk.

At the recent Commons evidence hearing on fisheries, Mike Cohen, representing the small-scale shellfish industry, explained that his fishers face a very different balance of risks and opportunities to some of those elsewhere in the business.

“A hard Brexit and some sort of catastrophic leaving with no idea how we are going to trade would be very harmful for some communities. Industry as a whole is one thing, but look at a small community like the one I work in, where we are entirely dependent on exports. If we end up in a situation where there is no technical regime for exporting, with no agreed paperwork and no inspection system, that could be very harmful.”

The reality is that most fishing communities in the UK are like this: small vessels catching shellfish to sell to the EU market. These ports—not to mention the communities that rely on these jobs—would benefit from continued close relations with the EU market. Britain should be seeking a Brexit deal that benefits all sections of the fishing industry.

This blog was originally published by Prospect Magazine here.